Three Generations of Wyeths Look Down

By Barrymore Laurence Scherer

October 2, 2013

SHELBURNE, VT — The Shelburne Museum is a magical place, a kind of backyard Smithsonian—from the more than 500-foot-long miniature circus parade of almost 4,000 handmade wooden figures to the fabled steamer “Ticonderoga,” last of the Lake Champlain side-wheelers, preserved down to its dinnerware and doorknobs in a grassy hollow.

Mainstream art is also part of this bucolic complex of architecture, folk art, old rural life and rolling landscape, which was founded, in 1947, on the collecting enthusiasms of the American Sugar Refining Co. heiress Electra Havemeyer Webb. A Greek revival mansion houses re-creations of rooms from Webb’s elegant New York apartment, complete with pictures by Corot, Degas, Manet, Monet and other masters. And nearby is the art gallery where, through Oct. 31, “Wyeth Vertigo” offers a compelling selection of 36 works by N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), his son Andrew (1917-2009) and Andrew’s son Jamie (b.1946), three generations of this celebrated dynasty. They reveal how the Wyeths have perpetuated a living tradition of late-19th-century Realism through the present, with N.C.’s vigorous imagery giving way to Andrew’s dreamlike alienation and Jamie’s quirky Surrealism.

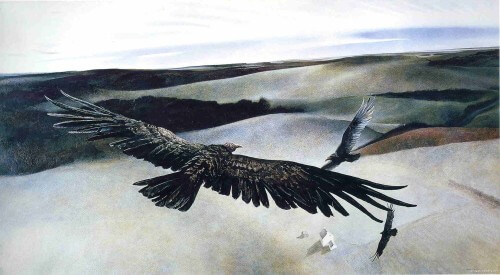

Central to the show is the titular idea of vertiginous height exploited by all three painters and symbolized by Andrew Wyeth’s “Soaring” (1950). Purchased in 1960 by the museum at Webb’s behest, it depicts a trio of turkey buzzards in flight—not from the ground looking up, but looking down at the birds as they soar above an isolated farmhouse hundreds of feet below.

Andrew had been instilled with an almost Pre-Raphaelite sense of meticulous realism by his father. “Don’t paint the arm,” N.C. exhorted. “Become the sleeve.” Hence Andrew prepared this work by closely studying and repeatedly drawing a dead buzzard. Nevertheless, his genius lay in his ability to imagine how the living birds in flight would actually appear from above, their circling implying that something lies dead on the ground.

Death as a way of New England coastal life was a Wyeth-family preoccupation. Works like N.C.’s “The Drowning” (1936), with its telltale empty rowboat washing up on shore, and Jamie’s “Spindrift” (2010), a dizzying aerial view of a spit of farmland surrounded by crashing seas, are but two views in the show implying the cruelty of nature. Drowning in the fearsome Atlantic was a daily threat to New England fishing folk. But Andrew’s “Winter Fields” (1942), which employs exaggerated perspective to place stark emphasis on a dead crow in a sprawling landscape, conveys the understanding that even away from the sea, to be in the middle of a field was to be alone and beyond help in a crisis or storm.

This unsettling sensibility possibly had its roots in N.C. Wyeth’s tormented spirit. By continuing the swashbuckling illustrative tradition of his teacher Howard Pyle, he had achieved celebrity and financial security in the early 1900s with his richly dramatic illustrations for Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” and “Kidnapped,” and an abundance of magazine covers. Canvases like “Just as the Baby’s Feet Cleared the Ground” (1923), showing a baby in an eagle’s talons “rescued” by an attacking wolf, exemplify the vigor that made N.C. an outstanding illustrator, especially his use of low viewpoints to achieve dramatic compositions. His successes enabled him to support his children’s artistic ambitions.

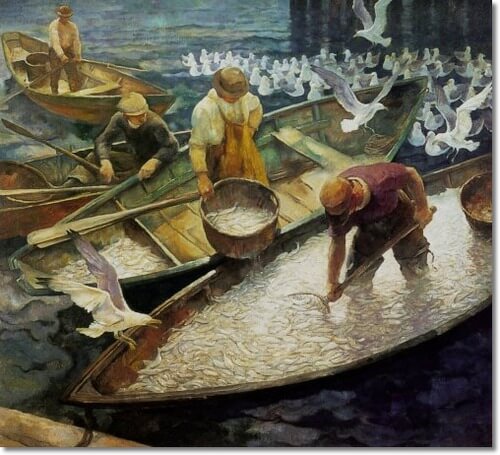

But as his son Andrew succeeded as a Realist artist in defiance of Modernist trends, the elder Wyeth felt trapped in the subsidiary profession of illustrator, and he grew to curse the commercial identity that pigeonholed him there, despite his attempts to escape. In “Lobsterman Hauling Trap Off Rocky Coastline” (1927) and “The Drowning,” we see him adopting Cubist ideas, fragmenting his imagery while preserving its narrative impact. “Dark Harbor Fishermen” (1943) is a late work that evokes North-European Renaissance painting even in its medium and support, egg tempera on panel. Viewed from a pier above them, four anonymous fishermen in rowboats, their faces hidden beneath hats, unload their day’s catch. It is a virtuoso representation of moonlight reflecting off the cold, wet swath of silvery fish and imparting an almost angelic white glow to the hungry gulls hovering about.

These and other works by the family make one ponder the relationship between illustration and the tradition of narrative genre and marine painting reaching back to the 17th-century Dutch, and to reflect on when a work is an illustration and when it ranks as fine art.

If N.C. was torn between his desire to be taken seriously as a Modernist painter and his Romanticist inclinations as an illustrator, his grandson Jamie seems easily to have married the two. Living at a time that worries far less about such distinctions, he applies his own Realist technique to startling imagery that often packs the spooky punch of gothic horror. In “Meteor Shower” (1993), the titular phenomenon occurring above a gloomy bayside village is deliberately upstaged by a menacing scarecrow, its immense black crow’s head craning weirdly from the gold-braided collar of an antique military tunic. In a more recent work, the crags and dark-blue swells of “The Headlands of Monhegan Island, Maine” (2007) form the backdrop to a nightmarish airborne procession of jack-o’-lanterns heaved off the cliff to their destruction on the rocks below.

In Jamie’s disquieting “The Islander” (1975), the land- and seascape are dominated by the fleecy, totemic head of a ram staring impassively seaward, like the resurrected spirit of the English Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt’s equally startling image of “The Scapegoat” painted a century and a quarter earlier.

The most celebrated family member, Andrew Wyeth frequently deploys his familiar palette of browns, grays and ochres to evoke the lonesome serenity of New England bleakness, which offers a visual counterpart to the lonely Americanism of Aaron Copland’s most famous orchestral music. However, the show’s most memorable work is a departure from this manner. “Night Hauling” (1944), painted during World War II, when dark nights were made even darker by air-raid blackouts, depicts a solitary poacher covertly stealing from a lobster trap on an inky black night. The poacher’s sharply averted head, the water cascading from the trap, even the trap’s interior, all glow with the phosphorescence of innumerable living organisms in the water. No printed facsimile can do justice to the almost supernatural, even colorful, effect that Wyeth achieved in tempera paint using a highly restricted palette of blacks, grays, blues and whites. It is a haunting work—not just for its subject, but for Wyeth’s ability to manipulate an opaque medium to convey a palpable sense of nighttime, soft luminescence and liquid transparency. This work alone would be worth the trip to Vermont.