Art (and Science) Talk with Greg Mort – The Official Blog of the National Endowment of the Arts

By Paulette Beete

June 20, 2012

“I think, ultimately, science and art ask the same question. They both seek a kind of beauty.” —Greg Mort

For painter Greg Mort, his art is grounded in the stars. His watercolors and oils reflect not just a deep fascination with the natural world, but also with the world that starts above the level of the clouds. As Mort reveals in the following interview, his long-term association with NASA’s art program happened after a visit to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum left him “mesmerized by the notion that NASA would commission artists to…be an eyewitness to space.” Mort’s work has been collected by the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Farnsworth Museum of Art, and the University of Padova in Italy, among other institutions. And, of course, his work also hangs at the Air and Space Museum as well as in several observatories across the U.S. The following interview is taken from a series of conversations with Mort over e-mail and via telephone.

NEA: What’s your version of the artist’s life?

GREG MORT: Art has always been something that I’ve kind of lived with; it’s a portion, it’s a part of, it’s an ongoing part of who I am. I think part of it was our household [when I was growing up] was where you had free reign to do whatever you want, and it was something my parents always encouraged, not really thinking I would be an artist. I think that’s the foundation for how I think about myself as an artist, as an adult, and even with my children—I encourage them to follow their passion.

Every day, even when I’m not working on a painting, I’m always in the process of creating something. All of my interests have an influence on the way I do things as an artist, and, as you know, one of my passions is science, so I’ve been able to weave that into how I think about my painting. It is something I never had a problem moving forward with. Sometimes you’ll hear about writers or artists having writer’s block or something, I’ve never had that problem; my problem is I have so many ideas that there’s not enough time to do all the different things I want to do, whether it’s just my painting, or some other creative endeavor. When I began being an artist professionally, it took some time for me to accept the title of an artist, because it was so much a part of who I already was, to put a label on it was hard for me to hold on to.

NEA: When did you start considering yourself a professional artist?

MORT: In the late seventies and early eighties, when I started to sell my work. It came about in sort of a strange way. I actually was building a sailboat, and I needed extra money to complete some parts of the boat. I had seen in my bank that they had artwork on the walls, so I asked the manager one time if I could display some of my paintings. Someone came into the bank and purchased all of the paintings, and that kind of made me think, “Hey, this is interesting!” So that was the birth of the notion that I could actually do it as a livelihood because [previously] that never really occurred to me, that was something that was just beyond the realm of possibility of a realistic endeavor.

NEA: What do you remember as your earliest engagement with or experience of the arts?

MORT: My dad loved to work with his hands. His ability to draw in a stylized manner struck me as magical. He would hand-carve pine airplanes complete with propellers that spun for my brother and me. I recall vividly him explaining the “twist” of the prop and how it drove the aircraft. Model-making has remained an important part of my life and has clearly influenced my thought process in painting. Creating/building miniature elements to study and stage paintings is as fulfilling as the painting process itself. These models range from architectural elements to islands at sea. In some ways I view my paintings as two-dimensional models.

What I’m trying to express is that the notion of creativity was as natural as breathing in our family. It’s hard to imagine a day without a project underway, however small or large. One’s imagination was celebrated, as was the “process.” My earliest teachers who identified me as the class artist and challenged me to create appropriate images for a holiday or lesson offered further encouragement.

NEA: To date what’s been your most significant or transformative arts experience?

MORT: This might sound simplistic but at the age of 17 I took my paint box out-of-doors and my vision of the world was changed forever. Until that time I had limited myself to copying from magazines, cereal boxes, books. These endeavors were excellent training exercises, but limited the true transposition that takes place when the interpretation is exclusively your own. In a very profound sense it was the first time I saw the world through my own mind’s eye. For me this was the awakening.

NEA: What artistic decision has most impacted your career?

MORT: [The decision] to never be afraid to fail. This philosophy is paramount. The fear of not succeeding is one of the most destructive obstacles to the creative spirit. The freedom and ability to flow with one’s creative energy, without question, allows endless doors to open. This is a mistake frequently made by those who ride the artistic train. You must be a passenger on the train, not the engineer. You must trust the journey via the rails before you without fear.

NEA: I know that you have a huge passion for science. What do you see as the relationship between the arts and the sciences?

MORT: I think there’s an amazing parallel between science and art, and if you look at art history, you can see any number of people, like Leonardo da Vinci, who was a scientist and an artist, and for me, both are almost one and the same. There’s this shared experience. There’s a scrutiny that science requires; there’s a scrutiny that art requires, and both have a passion for the notion of the question, and also the idea of knowing. I think that part of what each shares is looking for the underlying harmonies in nature. “What makes a tree a tree?” I think both science and art can ask that question in similar ways, although in science it might come out as an equation, or some other description. I think, ultimately, science and art ask the same question. They both seek a kind of beauty. [Science is] like getting to the heart of matter—what is matter made of—and I think art is kind of the same thing. We try to get at the essence of things. A large part of my artistic journey as a painter seems to find its roots in scientific inquiry. Combining my two great passions—art and astronomy—into a fulfilling blend of vocation and avocation has offered amazing inspiration.

NEA: How does this relationship between art and science inform your own work?

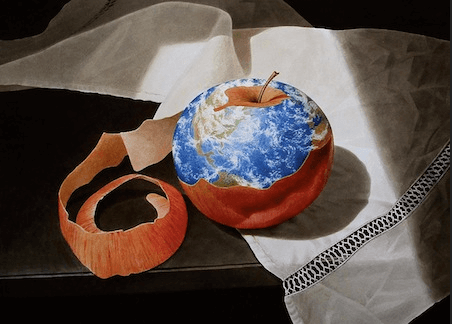

MORT: Around 1980 my love of science, in particular astronomy, began to clearly surface in my paintings. I became fascinated with the role of scale and its relationships in nature. Repeated forms reflecting natural elements in the realms of the infinite and infinitesimal consumed my imagination. Spirals, for example, are seen in galaxies and in tiny snails. The harmony of these interrelationships became one of the important focuses of my work.

NEA: How did you get involved with the NASA art program? What was the first work you did as a result of the program?

MORT: In the early 1980s my fascination with space travel brought me to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s exhibition titled Artist and the Space Shuttle. NASA’s foresight to commission American artists recording man’s newest celestial journey captivated me, and I was immediately determined to be part of the program. I was mesmerized by the notion that NASA would commission artists to, as they always like to say, “Be an eyewitness to space.” Boldness and naiveté blinded me to the fact that I would be following in the footsteps of American artistic legends such as [Norman] Rockwell and [Robert] Rauschenberg.

Knocking on endless bureaucratic doors finally led me to Robert Schulman, the director of the NASA art program, and his ultimate review and approval of my qualifications to join the ranks of NASA’s Artist and the Space Shuttle program. This adventure placed me on the NASA art team for an upcoming mission, the 1983 maiden voyage of Challenger STS 7, which carried America’s first woman into Earth orbit, Sally Ride. My first NASA painting was Morning Launch and it is exhibited at the Kennedy Space Center.

It has been an honor to continue my involvement in the program throughout my career, including more than twenty works of art that are included in global exhibitions mounted by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibitions program.

At some point, someone [at NASA] had the great wisdom to say, well, a thousand years from now, how cool would it be to have this historically and artistically documented through the eyes of artists. So they’ve commissioned not only painters and some graphic artists, but musicians, poets, all different venues of creative people, so I think it would be wonderful to have a record for future generations to see these events through the eyes of artists.

NEA: What do you think is the artist’s responsibility to the community?

MORT: First and foremost, I believe artists should reflect their time and space on the universal spectrum and speak to their moment in human history. An artist’s work should easily [reveal] which century or epoch it was created in. I would hope that in futurity someone could gaze confidently at my creations and realize they were products of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Artists have always had the ability to transcend language, culture, and the centuries. Since the dawn of our collective human memory, art in its myriad forms has expressed our hopes, our fears, and our loves while also serving as an interpretive record of the world around us.

You can see one image and, you know the old saying, an image is worth a thousand words, a picture’s worth a thousand words, I think it’s truer than ever. I think art remains a strong tool, and it is an artist’s responsibility to use their ability to make statements—whether it’s about the environment, or whatever they choose to speak about. It’s their duty, almost, to portray and communicate. If you think about the really ancient forms of communication, of course they would be the cave paintings, this is pre-language or writing, humans have always had this tendency, this ability to communicate and represent the concerns of our times via imagery.

NEA: What’s the Art of Stewardship Project?

MORT: In this the new millennium, the realization that we indeed live on “one world” carries with it responsibilities never dreamt of by our distant ancestors as they expressed their visions on cave walls and with carved fertility icons. We now recognize the fragility of our planetary home and the profound role each of us plays in the drama of life on Earth.

Now more than ever the artist will play an ever-increasing part in a cast that must include all of humanity.

About ten years ago we founded the Art of Stewardship Project (TAOS) calling out to those who speak the universal language of art. TAOS invites artists…to use their talents to raise awareness, inspire, and celebrate our role as stewards of our tiny oasis in space. At this point in history no challenge is more important or more immediate in nature. Our very survival depends on it. My role as guide of TAOS has offered me humbling inspiration with sharing opportunities from the poorest villages in India to the pristine walls of the United Nations. Through forums at educational and environmental institutions and my collaboration with the global freshwater public forum Circle of Blue via the Clinton Global Initiative, we have made more of an impact than I had ever dreamed possible.

Artists worldwide are invited to help bring the notion of stewardship to the forefront of our conversations and consciousness.

NEA: Conversely, what do you think is the community’s responsibility to the artist?

MORT: Society benefits one hundred fold by nurturing, exploring, and respecting the positive power of the communicative experiences artists offer humanity. Art can often be prophetic, providing unimaginable visions of the future as in the case of Jules Verne. It transcends language and cultural differences and remains an eloquent yet elemental way to reach across every cultural boundary or man-made border. Supporting a community’s artistic energy is paramount because it leads to discovery, awareness, and harmony.

NEA: Any advice for beginning visual artists?

MORT: The creative forces that lay at the heart of what we describe as art flow in an unending stream. For those who might embark on that stream/journey, I say this: Follow your passion and intuition and take advice sparingly. Many, who would sincerely like to help, in the end, can’t possibly know the forces at play within you. Trust yourself. If you must engage with others in partnership, only do so with the confidence that they support you with unquestioning devotion to your cause and creative vision. Be messy. Flourish in chaos as order and limits are among the bastions of the non-creative. You know what has to be done.

For me, there’s never been a point where I really have to make myself do this. I just sort of always bubbled over with enthusiasm. People will ask me, “Well, what’s your favorite painting?” and the obvious or non-obvious answer is the piece I’m working on now because that’s when you feel the incredible surge of birth, of creativity. It’s not so much the thing you did a year ago, or ten years ago, although you might be very proud of those things. So much of it is the act of creating. The hanging of the picture, or the picture being in a collection in a museum, is icing on the cake. The real guts of what you do is the moment of creation.

NEA: At the NEA, we believe that “Art Works.” What does that phrase mean to you?

MORT: My community is important to me, and I am privileged to support it with my art. Both of the two fine galleries I have been “married” to for more than twenty-five years—The Carla Massoni Gallery and The Somerville Manning Gallery—have collaborated with The Art of Stewardship Project to build environmental awareness through the arts. When I look around the arts community I see similar efforts being replicated over and over again. Artists and their art can and do make a difference.