“American Masters” Exhibit in its final days at Somerville Manning Gallery

By Catherine Quillman

West Chester Patch

May 24th, 2012

For more than 30 years, the Somerville Manning Gallery has a been a case study in how to display and sell art in a region that happens to have its own art identity known as the Brandywine Tradition.

From the start, the gallery – named for its joint owners and housed in an historic mill – has been intimately associated with the artists in the forefront: the Wyeth family. Many of the early group exhibits have reflected the late Andrew Wyeth’s influence on artists who have captured the Brandywine region as a kind of Walden-Pond-like microcosm of rural beauty. That is just one reason why it’s worth dropping those weekend chores and taking the time to see this exhibit, which closes June 2nd.

Displayed in the gallery’s two large rooms overlooking the Brandywine, “American Masters” offers a mini history of many of the key art movements that took place in the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. All the artists are represented in major museums, but seeing their work here, in the relatively small confines of gallery, has an unusual impact. I found it fun to play “name that artist” but I also came to some conclusions seeing the work together. In many of the works, it was easy to see how American art is rooted in regionalism or a sense of place.

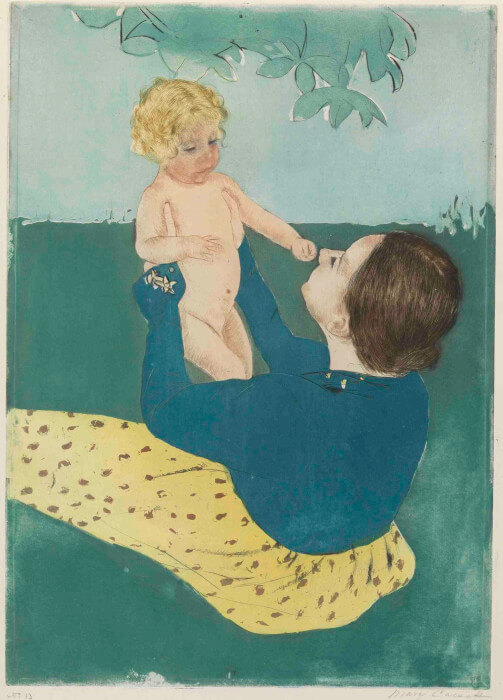

For instance, there are works by well-known masters such as Mary Cassatt, Edward Hopper, Maurice Prendergast, and John Singer Sargent – those artists alone point to the gallery’s strong connections in the art world. There are also lesser-known artists whose work would not otherwise be shown in “Wyeth country” such as the New York mixed media artist Donald Sultan (b. 1951), whose “rich use of black,” as it is described, is sometimes actually tar.

The exhibit label explains Sultan’s use of black backgrounds to highlight still-lifes of fruit, flowers, dominoes and other objects. Another important but off-the-radar artist is Theodoros Stamos, a contemporary of Jackson Pollock who is described as an artist who “bridged” the first and second schools of Abstract Expressionists.

It is interesting to see the artists of the 1940s and 50s – Andrew Wyeth’s contemporaries – in the same room with realists such as Hopper (represented here with 1941 charcoal sketch “Near Eastham”). Critics have said that the “AE’s” had a major influence on realists in the way they delineated a sense of space. The variety of works here can thus allow you compare movements and influences. For instance, Andrew Wyeth’s watercolor, “Study for Winter Fields” captures a branch and Chinese Lantern plant with precision and depth, bringing to mind Hans Hoffman’s advice to lay down lines to create the “push and pull” tension of a painting.

Viewing works by major artists, in a gallery setting (and knowing that the works are all for sale), reminded me that artists don’t create works for museums, nor do they necessarily know that their work is a part of an oeuvre (to use one of those words that got you extra credit on term papers).

The gallery includes exhibit labels instructing you to notice, for instance, the characteristic details such as Edward Hopper’s “architectural elements” and Milton Avery’s joining of “modernism with folk art.”